Let’s try an experiment: Close your eyes, and in 10 seconds think about your reaction to the following term: “team building.”

[Okay, you can stop now.]

[See, this is the problem when you tell someone to close their eyes and do something while they are reading; they can’t actually see when the time is up and its time to move on.]

[But enough dissembling. Let’s get back to it.]

So what did you come up with? Images of engagement, collaboration and interactive exploration? Or memories of awkward interactions, embarrassing exercises and superficial social niceties?

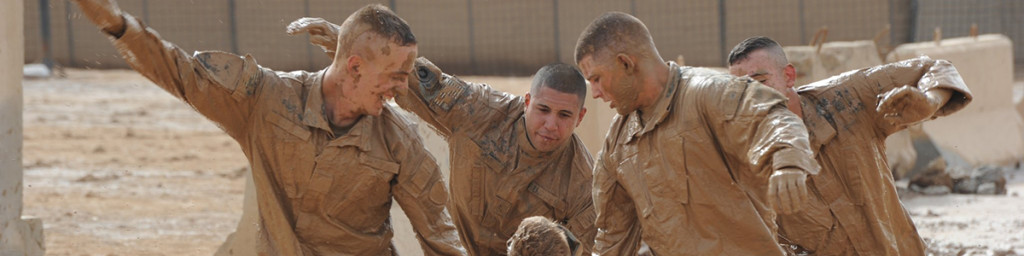

There are a great many sins that have been committed under the rubric “team building.” Retreats, ropes courses, orienteering, trust exercises, sharing of intensely personal information, role playing exercises… if you can imagine it, it’s been done. Organizations invest tens of thousands of dollars in such exercises every year, with the theoretical intent of enhancing trust and improving team performance.

There is only one problem with all of this, however: for the most part, team building exercises don’t actually work. What’s worse is that we’ve known about this for some time, and yet repeatedly engage in the same behaviours, somehow expecting a different outcome.

Specific and deliberate team building approaches have a number of challenges inherent in their design and delivery. In particular is the fact that they are often separate, distinct and isolated events. The team is taken out of their specific work context in order to focus on their team interaction and effectiveness. The hope and expectation is that they then return to their work environment with new-found understanding, enlightenment and commitment to the task and to each other.

The very design of team building exercises is often part of the problem, however. Team building exercises may build temporary cohesion and cooperation, as groups work to solve specific challenges or address obstacles designed as part of the team building intervention. The challenge is that this focus in the moment doesn’t necessarily translate into sustained behaviours back in reality. My helping you across a rope bridge today doesn’t in any way mean I’m going to help you improve your code tomorrow.

Worse, the design of team building exercises can actually be counterproductive. Exercises that are designed with an expectation of promoting ‘healthy competition’ can actually fail. What is supposed to be good natured sport can result in the intense winner-take-all entrenchment of factions. The result can be the creation of divisions that previously didn’t exist, and hostile confrontation—sometimes disguised as good-natured trash-talk—between sub-groups.

Bottom line is a question of whether team building exercises actually result in the behaviours that are desired. A significant question here is whether the sessions as they are designed in any way relate to the behaviours that are needed or expected in a work context. Off-site retreats that focus on irrelevant behaviours are often nothing more than team building for the sake of team building.

All of this is not to say that team building per se isn’t appropriate. It is more an issue that what is done under the label of team building is frequently misguided, inappropriate or irrelevant. If that’s the case, however, a larger question we have to ask is: what behaviours are actually useful and productive? If team building can be effective and relevant, then when is that the case? And what are the approaches and aspects that actually make a difference?

A meta-analysis of team building performed by researchers a few years ago provides some intriguing and important insights. Integrating results from twenty research studies, the research attempted to ask a fundamental question: does team building work, and if it does, then in what circumstances?

What the study found was that team building interventions have the greatest impact when focussed on two specific activities: role clarification and goal setting. Role clarification involves being clear about what the contribution of each member of the team is expected to be, and defining expected interactions, communication and collaboration between team members. Goal setting involves clearly defining the expected objectives and outcome of the team, providing clear and concrete understanding of what the team is expected to accomplish.

What is significant in both of these results is that team building is not separate and distinct from the work of the team. It is, in fact, part and parcel of the work of the team. But team building works best in figuring out how the team is actually going to work on the actual task at hand.

This is an important insight, and one that needs to be highlighted and reinforced: team building is not separate from the work, it is the work. The act of actually starting out on a project or undertaking, clarifying the problem to be solved and the role and contribution of each player in solving it, is what makes the most difference in building team cohesion and effectiveness.

That means that we aren’t trying to build context-free understanding of who you are. We are trying to understand who you are in relation to the work we are about to undertake. What is the background and experience you bring to the table to solve this exact problem? What is the contribution that you can make to this project? How are we organizing to tackle the work, how will the team interact and what are the expectations and commitments of each team member?

A significant challenge in addressing team building is that a lot of the language that we use in talking about projects and the organizing work separates the team building from the team doing. It’s not just in how we think about team building sessions as separate from work (and often separate from the office). How projects get started often go through formal and distinct stages. We talk, for example, about team ‘kick-offs.’

The implication, for most of us, is that the kick-off of the team is separate once again from the later work of the team. And yet, if this is the where we actually start establishing role clarity and conducting goal planning, this is possibly the most critical part of the project. Get this right, we have given ourselves the best opportunity for success; get it wrong, and we are almost certainly doomed for failure.

The importance of the start of teams was reinforced in research by Connie Gersick. Most critically, she found that teams entrench beliefs about commitment, productivity, focus and urgency from the very first meeting of a project. The tone from the outset represents a form of inertia, and is highly resistant to change until about halfway through the project. This led to a very different view of how teams develop, and how they evolve over time.

Until Gersick’s work, one of the dominant views of team building was that of forming-storming-norming-performing. Defined by Bruce Tuckman in 1965, this fifty-year old model is surprisingly enduring, but flawed. What Gersick found was that teams don’t progressively move through these stages in sequence, nor does each stage involve similar time or effort to move through. They might hit some of the stages some of the time for some period, but not in the manner Tuckman suggested.

Instead, what Gersick found is that teams experience ‘punctuated equilibrium.’ In other words, we have a happy place we like to stay in, until we get a short, sharp shock that forces us to go somewhere else. In the context of teams, this reinforces that the tone at the beginning sets the experience through the initial stage of the project. This stage is surprisingly stable, and consistently lasts about halfway through the project. And that’s where the shock quite frequently occurs.

What is common for many teams is a realization, usually at about the midway point of a project, that progress is not being made in the manner that was expected. At this stage, there is an acknowledgment that if things do not change, then there is a very high risk that the team won’t meet it’s goals. This ‘mid-point transition,’ as Gersick defined it, is critical to subsequent reformulation of approach and recommitment to the focus of the team. Where teams have not performed well, there is a reestablishment of focus and reenergizing of effort to get the project done.

What’s critical to the mid-point transition is that it be dramatic; it has to have enough energy to overcome the teams original inertia and shift them to a new way of thinking and doing. That means that the realization needs to be visceral, emotional and personal. There needs to be a real fear of potential failure, and sufficient focus and commitment to avoid that outcome, if the mid-point transition is going to occur.

Even better, though, is avoiding that situation completely, by getting it right up front. That means setting the tone and creating the culture, energy, commitment and focus that allows the team to successfully coalesce. There has to be emotional commitment to the task and each other, that crystallizes at the outset.

Starting projects, sending teams to off-site retreats and holding kick-off meetings without content, energy or focus is simply going through the motions. It is paying lip service to what it actually means to be able to build a team. Teams are not built in order to go and do the work; they emerge as a by-product of doing the work, and experiencing the immersive results of focussing and committing to jointly getting something difficult, awkward and complicated done. In particular, it is a product of the very messy process of figuring out what to do, and how to work together, to get it done.

This means that team building isn’t an abstraction. It’s not separate and distinct. It isn’t formal and structured. It happens by working, together, to sort out what, and how, and by whom.

The research done in the initial study on what works in team building found other influences on team building that had an impact, although to a lesser degree. Building interpersonal relationships and problem solving were also activities that contributed to positive team outcomes.

Building effective interpersonal relations is an interesting one, because it gets at some of the behaviours that traditional team building theoretically develops. Increasing skills of teamwork, communication, trust and confidence are all part and parcel of developing interpersonal relations. These are all best developed, though, in the context of the task at hand. My ability to work effectively with you in a team is not (usually) a product of whether I can trust you with my life, or to catch me if I fall backwards. It’s about can I trust you to do your part of the work, to bring your expertise and insight to the project, and to honestly share and provide feedback.

Bottom line, what works best in team building is the assembly of a qualified, capable team that can do the work, is committed to the work and is invested in getting it done. For the team to function well from the outset requires not just setting—but also modelling and experiencing—the levels of commitment, focus, productivity and interaction required to deliver successfully. This is not done in a separate, artificially structured exercise. It is best brought about by recognizing and defining the work of the team, and by treating the formation and development of the team as an integral part of the work.