What if you never forgot anything? Take a couple of seconds to think about that; imagine what it would be like to have everything that you had ever learned available to you at a moment’s notice. Consider what it would mean to have access to every concept you ever encountered, every insight that you had, every argument you were exposed to—or at least, those that you found relevant and meaningful to your interests. How would that change your approach to your work, to your life and to your creativity? What would it mean to always know what you know, to not forget, and to keep building from there?

Sounds like a tall order, doesn’t it? But let’s build on that for just a second. Take a few more moments to reflect on what it would mean to know where those ideas came from. What book you originally found them in. What quote inspired you to pull out your highlighter—not that one, but the special highlighter—to emblazon its meaning in day-glo colours on the page? What were you thinking when you first read that idea, and how has your thinking evolved over time? How significant would it be to have instant recall of how your thinking transformed?

Before we wrap up this little thought exercise, let’s add one more proposition to our increasingly far-fetched premise. What if you never ran out of ideas? How valuable would it be if every time you had a creative project, you had several different avenues to explore? Imagine already having identified gaps to investigate, contradictions to address and new insights to develop in your writing. Consider already having an inventory of research to delve into, plans to pursue and proposals to advance. What would it mean to have enough interesting and compelling activities on the go that you were never blocked and seldom bored?

If all of that feels too good to be true, I know exactly where you are coming from. I certainly have my own healthy dose of skepticism on the subject. Nonetheless, these are the assertions that Sönke Ahrens essentially makes in his book “How to Take Smart Notes.” The ideas in the book prompted my explorations of last week, along with a promise to further examine the mechanics of how the system that Ahrens describes works.

To be clear, the system we are exploring is not the work of Ahrens. That honour goes to a scholar of the last century (and, arguably, the last millenium). Niklas Luhmann was a German sociologist whose self-declared research effort upon joining the faculty of the University of Bielefeld was a “theory of society,” with a timeline of 30 years and a budget of zero dollars. Grand theories of society are the holy grail of sociologists; we are firmly veering towards magnum opus here. Thirty years later, on schedule in 1997, he published his “Theory of Society” (more literally translated as “They Society of Society,” but we shan’t go there).

While Luhmann might be relatively well known in very specific circles of sociology, his larger claim to fame derives from the way he worked in developing the chapters of his theory, and approaching his work overall. He characterized his slip-box system (or Zettelkasten) as a collaborator, not just an inanimate filing system but an active partner in his research, his thinking and his writing. Everything he did, he did in the slip-box.

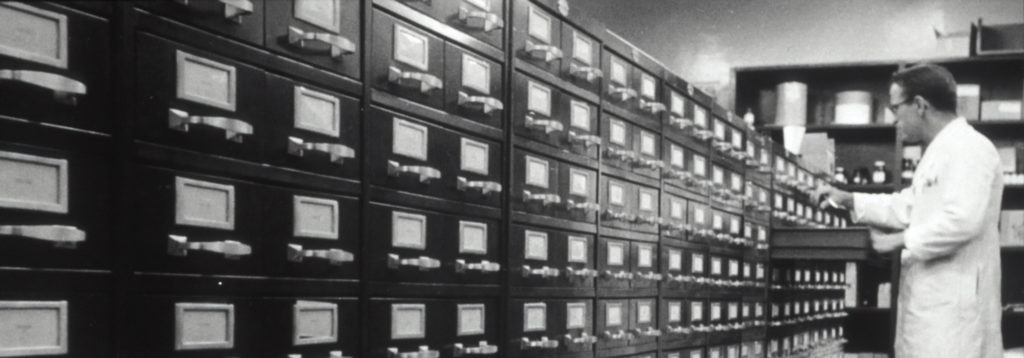

The mechanics of how this worked—and the value of working in the way of Luhmann—is what Ahrens dedicates his book to studying. On the face of it, the slip-box system is simplicity itself. Notes on index cards, stored in largely sequential order (with a number of exceptions, but the point was that there wasn’t an overarching hierarchy so much as a web of ever-expanding ideas) in a series of file drawers. (Again, it’s useful to remember that this was a system of the last century, developed beginning in the 1960s and not seen at the time as a candidate for automation).

In the course of his work, Luhmann’s system grew to some 90,000 index cards, which embodied the essence of his work. It captured what he read, what he found interesting, what he thought about those ideas, and how he made connections between new information and what he had previously read . While that number might sound impressive, it was the progressive accumulation of a lifetime of reading, thought and discovery. A few cards every day led to an impressive and intimidating body of knowledge.

Apart from Ahrens’ book, there are numerous introductions to the system (searching the Google for “Zettelkasten” will take you down an impressively deep rabbit hole). Individual ideas are captured on each note, as if you are brainstorming with yourself (which arguably you are). Notes get filed with like notes, with a sequential numbering system that both orders how notes relate to each other, and identifies where branches of thought depart. While ideas coalesce around an individual topic, connections are also made to other entries in the system. The result is a bottom-up exploration of the topics that interest you, growing organically as you read more, think more and reflect more.

Reviewing Ahrens’ book and the principles of the system, there are a few essential concepts of organization that stood out for me. One of the most essential was the bottom-up nature of the system. For most of us, the closest analogue we have to a slip-box is the card catalogues that those of us of a certain age would utilize when visiting the library. The catalogue served as your guide to the structure of the library, based on either the Dewey Decimal System or the Library of Congress. Regardless of the approach used, books were archived and organized by topic. The structuring of libraries is based upon an archival ordering of knowledge into pre-determined topics.

The slip-box is by contrast built around interests. There is no inherent structure up front, and what is stored within the system is what emerges based upon what you as its owner find relevant and meaningful. Connections between topics transcend structure. The point of the slip-box is not to impose structure, but to allow meaning to emerge. The question for any item to be stored is not “to which category does this belong?” so much as “how do I make sure that this idea presents itself to me again when I need it?” You are not filing for organization, but for retrieval.

Another key concept that stood out relates to where we came into this discussion: the purpose of the notes, and the kinds of notes that we take. As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, the essential structure of my notes is two-fold: I have ephemeral notes that generally get captured in whatever journal I am currently working with, and I have the notes that define the structure and ultimately guide the creation of whatever project I happen to be working on.

Luhmann’s slip-box method also recognizes a hierarchy of notes, built around what guides the creation and maintenance of the system. That starts with what Ahrens refers to as “fleeting” notes. These are the notes that you might take when reading a book, attending a lecture, listening to a podcast or watching a presentation. They might be direct quotes, or capture the essential insights that you gain. You might describe an idea being expressed, or your reaction and response to that idea (whether reinforcing, questioning or expressing indignation).

The point of fleeting notes is that they are made in the moment. They aren’t intended to last, and their significance will likely fade over time as whatever you capture gets further removed from their context. For fleeting notes to have value, they need to be revisited and reframed to preserve the context in which they were made. You need to make meaning of them. That means going back over your notes, and translating them into something that will continue to be relevant long into the future.

The notes you capture and reframe about any one source are “bibliographic.” They are your summary of what was meaningful and relevant about a particular work (written or otherwise). This does not need to be—and arguably shouldn’t be—an exhaustive distillation of what was said. The essence you need to capture is what matters. What is new? What is different? What is controversial? What raised questions for you? The notes you make and keep are inherently a process of editing: you filter them through what interests you, what you care about and what you want to further explore. A book or presentation that adds little to your understanding might get brief attention, if any. Something that rocks your world is going to fill up more than a few slips as you process what it means to you.

Finally, there are permanent notes. Where bibliographic notes highlight what was meaningful and relevant in a particular work, permanent notes are where you make sense of it in the larger context of your system. This is where you translate the ideas of one person into the integrated connectedness of your slip-box as a whole. This might involve the inclusion of new ideas, the contrasting of opposing perspectives, the elaboration of points that you haven’t yet considered or questions and gaps that have now emerged in your understanding.

That brings me to the concepts that I found challenging, although that challenge was positive in that it made me think. Firstly, there is no space within the system for project notes (which, as I’ve noted previously, are pretty much essential to my worldview thus far). That’s not to say that project notes don’t happen; they do. They just don’t stick around. While they have slightly more staying power than the ephemera described as “fleeting,” their usefulness lasts only so long as the project they support.

In many cases, project notes will build on the ideas, questions and gaps suggested by the permanent notes. Whole arguments may be extracted wholesale from the slipbox, and be related in ways that advance the particular project. Once the results are produced, however, the notes become relatively meaningless. The enduring ideas are still encapsulated in your permanent notes. The project notes can now be deleted (for the brave) or archived (for those with less intestinal fortitude) at the conclusion of the project.

This echoes in many ways how I relate to my project notes overall. I archive them, and they are still there. The likelihood of my ever going back and looking at them, however, is excruciatingly remote. The results of the project are what matter, the notes were a means to an end, and even if I pursue a similar project in future, there is every likelihood that I am going back to first principles. The difference is that my first principles start with a blank piece of paper, not a robust system of permanent notes built up over time.

Where I struggled with for a time was understanding the idea of connections and how they work. The structure as described felt a little too bottom-up; that there was no way in, or at least not an obvious one. I certainly grasped the assembling of related notes around emerging topics in a progressively evolving sequence, and the connecting of ideas to others that show up along the way. What I was missing was the entry point.

There are two essential components guiding access that get mentioned, but arguably could use some additional elaboration in how Ahrens explains the system. First, there is an index of major topics. This isn’t a going-in categorization, but it is an emergent pointer to the major themes and ideas contained within the system. What that index points to is topics that guide navigation within the system. Whatever your particular interests might be, the topic cards will point you to the major ideas that represent those ideas within the system. These are their own source of insight, as your perception and understanding of a topic evolves over time. Maintaining these can provide understanding into the evolution of your thinking.

The slip-box system developed by Luhmann and espoused by Ahrens is a fascinating one. The appeal of an on-going reference to continue to draw on is undeniable. This is not to say that there isn’t a fundamental challenge: taking the time to develop it. It takes work and effort to translate fleeting notes into permanent ones. That is why I still have my journals of the last decade or so; they are the only record I have. But my memory of what is inside them is fleeting. The notes may have made sense at the time, but it is an open question as to whether I would remember what was intended by many of them today.

Building a slip-box requires investing in a larger process of reflection. It means establishing a discipline of asking “what does this mean for me?” and taking the time to write that down. That is an investment that has thus far eluded me–which is interesting in and of itself.

I have a doctorate. I know in theory how to do this, in that I have engaged in the discipline of reading, note-taking and reflection for a time. My dissertation, however, ultimately took on the dimension of just another project. Rather than serving as an initial (or expanding) knowledge base upon which to continue to build and evolve insights, it became just another archive. Much of the work to date builds on the ideas I researched and the reading that I did, but so much of what I do still goes back to the beginning.

This represents a compelling insight and leaves me at a challenging crossroads. I’ve been exposed to an alternative way of working. While there is appeal (and a deceptive simplicity) to what has been conveyed, following through represents a lot of work. More particularly, it involves working in a way that I have not done on a sustained basis before. The process of reading shifts from one of passive absorption to active engagement with the text. Engagement means taking notes that mean something to me, not just a wholesale regurgitation. Meaning comes from actively and continually taking the time to reflect, to consider and to learn.

There are benefits to a second brain. There are costs to building one. The question is: do you unleash the monster? Or do you stick with what is tame and safe?