Here’s an interesting question: How did you get to the you that you are today? Specifically, when you think about the career you are in, the job you perform, the roles that you play: what allows you to be successful? What are the formative experiences that guided you? What are the concepts you learned, the skills that you developed and the insights you gained that allows you to naturally and easily do what other people find baffling?

It’s an incredibly important question to consider as we think about developing people, supporting change and encouraging the development of new capabilities. But it’s not one that we necessarily consider. And that’s potentially problematic.

Think about how we roll out projects or support transitions and organizational change, for example. We may alter structures, modify processes, change out systems and develop approaches and expectations that require wholesale shifts in behaviour. And yet we presume that if we explain the logic of what we are doing and provide some foundational workshops that explain what’s being implemented and how to use it—preferably in three hours or less—then transformation will magically occur.

Sadly, change doesn’t magically occur. Sometimes it doesn’t occur at all. And while we recognize that change is difficult, that old habits die hard, and that people default to what they know when threatened, insecure, stressed or uncertain, we don’t do anything differently.

We encounter similar challenges when we try to support the development and growth of our staff. For all the theories that exist around career development and all of the bromides promoting life-long-learning, this is also neither straightforward nor simple.

A case in point would be my efforts to grow my company. I’ve been a consultant pretty much my entire career. I founded Interthink nearly thirty years ago, and I’ve been responsible for developing most of our consulting offerings, defining most of our practices and supporting the majority of our client engagements. The core philosophy of what an Interthink engagement is, what it looks like, how clients should experience it and what a quality result looks like is ingrained in my DNA.

And while that’s all well and good as far as my involvement in a consulting project goes, the challenge is replicating that in others. As we added staff, what I wrestled with was how to teach the philosophy, illuminate the thinking process and instil the skills necessary to allow others to understand, embrace and replicate the work. This isn’t to say that they wouldn’t bring their own personality, perspective and insights to the table. But the essence should be that a client of Interthink should know, recognize and embrace that they are a client of Interthink.

That’s what we try to do with any organizational practice. It’s what we work towards when we build and enhance maturity. It’s what we strive for when we are talking about promoting and ensuring consistency. It epitomizes the difference between “this is what it looks like when this person runs your project” vs. “this is what it looks like when this organization delivers your project.”

The more complex the work to be done or the solution to be delivered, the harder that outcome is to realize. You can prescribe a consistent customer experience when you are selling burgers and fries. It gets more challenging when you are tailoring and adapting solutions and service offerings. And it becomes profoundly more complicated when what you are delivering is unique, contextual and complex. The more the answer depends, the more flexibility is required to get to a solution it depends on, and the less likely that the experience of getting to that solution will be similar from engagement to engagement.

When I originally started hiring staff, my presumption was that I needed to get them to be more like me. And that was one of the most bone-headed and misguided propositions I have ever come up with.

In theory, it sounded good. If you can teach people to think like you, approach problems the same way, bring the same principles to bear and exercise the same judgement, then everything should be totally replicable. But here’s the thing. You can’t. The only person you can change is yourself, and even that is more than a little complicated to pull off.

But how do you build those skills. Or, phrased another way, how did I get to here? What would one need to replicate if one wanted to build another me? That story is rife with its own intricacies and complexities.

My career path to here has not been defined, predictable, orderly or in any way normal. I am a generalist. I am a nerd. I am a bookworm. I am relentless curious. And I’m acutely conscious of everything I don’t know (but wish I did) and can’t do (but genuinely want to do).

Go back to my early years, and my interests were in science. I was fascinated with the natural world. Geology, for a while. Bugs, too. Birds. And then (when I was about 10) along came computers. Specifically, my school temporarily borrowed (for perhaps a month or so) two Commodore PETs with 40 character green screens, cassette tape storage devices and an unquestionably primitive amount of computing horsepower. I was fascinated. I was smitten. I wanted to learn everything I could about them. I bought books. I learned programming (some rudimentary interpretation of BASIC, at the time). I found adults who had access to the same technology, and befriended them, and wheedled my way into offices after hours so that I could play with them (and yes, I was still about 10).

By the time I hit high school, I was an inveterate geek. I got hired by my school to develop programs to manage class scheduling and allocation of electives. I acted as tutor for most of the computer science classes (through Grade 12, when I was in Grade 9). I still wangled as much computer access as I could, including keys to the high school computer lab, where you would find me most weekends.

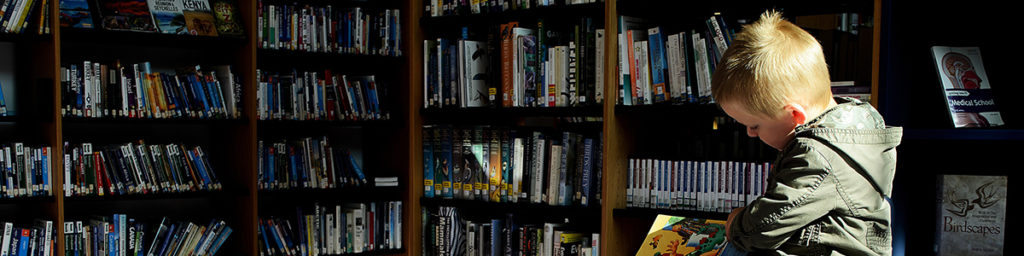

On the bus to and from school, you would find me reading. About computers. Science fiction. Fiction fiction. Non fiction. Biographies. More computers. Whatever I could get my hands on. I also managed to immerse myself in the world of interactive fiction, courtesy of Infocom and the Zork trilogy. I plotted how to build similar games. I struggled with the idea of programming to manage the containment, possession, location and disposition of objects (which would become much easier to handle once object-oriented computing was invented).

And then a switch flipped. Through a friend (who at the time was a prime source of access to computers and music and popular culture) I discovered theatre. Specifically, he was running sound for the dance recital for his mother’s ballet school. It was suggested that if I went to the theatre, I could find him backstage. I did. I found a whole other world and a whole new sense of meaning and purpose.

A two hour visit turned into a multi-year immersion. For the rest of high school, I never left that theatre. I became involved in a local musical and dramatic society (of which I was the youngest member by some 15 or so years). I knew something about sound and audio, and became the resident sound technician. I learned lighting. And stage management. And production management. I would eventually—much, much later—come to realize this was project management by another name. So when I claim to have been managing projects from the age of 14, I’m not even exaggerating. I just didn’t know it at the time.

My interest in theatre took me all the way through university, which was its own eclectic experience. I studied acting because I had to. I took every course in technical theatre because I wanted to. I studied dance because it intrigued me. Russian culture because it meant I didn’t have to study French. Computer science because I could do it well. Psychology interested me not at all (I’ve undergone a remarkable transformation on that front since). Math interested me a lot, because I did university-level algebra and calculus in high school (although I also came to appreciate that math departments frown on arts students doing well in their classes, which also introduced me to the subject of politics).

What I particularly learned in university, though, was how to make connections. How to see ideas that—while relevant in one context—could be explored and applied and used in ways far beyond their original purpose. In studying dance, for example, I learned the process of movement notation that choreographers use to commit human movement to paper. While I never choreographed, I immediately borrowed the form and expression as short-hand for documenting the movement of actors while stage managing. It was never designed for that, but it worked incredibly well.

I learned structure and relations in university. I remember vividly a computing science class where a hapless prof was struggling to teach entity-relationships modelling to a large class of students that desperately wanted to be anywhere else. One early morning I had an epiphany about how understanding data and relationships was related to but transcended process models, logic structures and tree diagrams. Another language opened up, along with a new way of seeing and relating to and documenting abstract concepts in the world.

I’ve used those concepts ever since. I remember enough from a first-year university class that I can still build an entity-relationships model in fifth-normal-form, and then de-normalize it into something you can actually build a system with. And non-sensical as that may sound to the lay reader, I’m also confident in the fact that the previous sentence is not only grammatically correct but logically consistent and entirely accurate in its meaning.

My journey has been, in many respects, unique. It has been eclectic. There has been no overarching strategy and no guiding hand. I’m fairly certain, in fact, that my parents orbited the pit of despair when I announced my intention to study theatre at university (my step-father really wanted me to be an accountant, not because of aptitude so much as earning potential).

It is a point of pride that I have a bachelor of arts in drama and theatre arts, a three-year degree that it ultimately took me eight years to earn. As much as it is also a point of pride that twenty years later, I also earned a doctorate in project management, from a school of sustainable development, with a thesis that wove together strategy, decision making and psychology (a subject that unquestionably grew on me over time).

At the same time, I marvel at the number of people that I encounter (particularly in project management) whose career path echoes mine. Who studied theatre, found management and became project managers. Or who pursued a liberal arts degree but are comfortable in the sciences. People who followed their interests and passions, learned how to think and reason, and took that skill and ability and applied it in manners and ways that went far beyond what was intended or imagined.

I used to downplay that I had an arts degree. I don’t anymore. I am a product of my formative experiences. More specifically, I’m a product of ALL my formative experiences. At the time, many of them no doubt seemed nonsensical. And they arguably were, even to me. I pursued things that interested me. I mined those experiences for insights. I applied those insights where I could. I adapted them when that was relevant. And I learned how to think.

I learned how to think structurally and logically. I became comfortable with thinking inductively and intuitively. Somewhere along the way, I learned to accept uncertainty and risk. I had confidence in my choices, a willingness to take a leap of faith and enough hustle and ambition to make of situations what I could, and figure out how to land on my feet.

And that’s how I became a consultant. And that’s why I can do what I do. And why I know what I know. And how I am humbled by all the stuff that I don’t know. But most importantly, why I’m confident that when the time comes, I’ll ultimately figure it out. Because if we do it right, that’s really the only thing we take away from our educational years that is genuinely of value. We learn how to learn. And that’s everything.