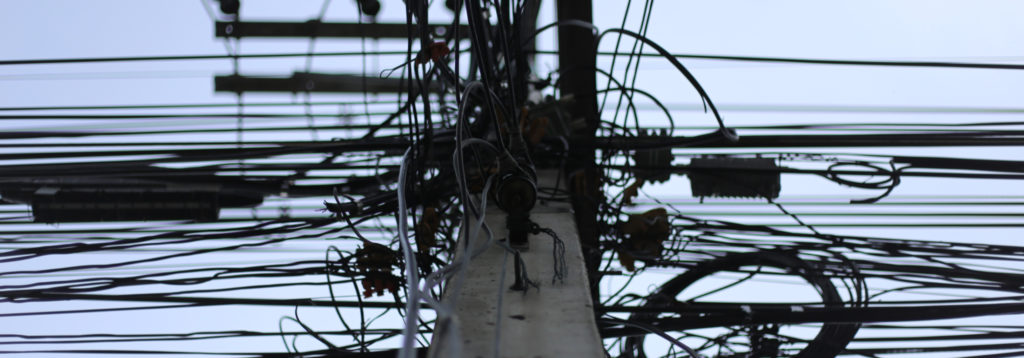

I’m working through a fascinating project right now. It is a big, extremely complex and very important problem for the client to solve and it has an inordinate number of moving parts. The client wants clarity so they can make some decisions. But there is some messiness that needs to be worked through first.

Correction, there is a lot of messiness. The focus of the work is fundamental to who they are and how they function as an organization. Different departments have different approaches and practices and use very different tools to get things done. They have evolved divergent philosophies for the things that they do, and consequently try to accomplish very similar things by relying on dissimilar ways of functioning.

The result is that to get something done when engaging with the organization you need to know what you are trying to accomplish, which part of the organization is responsible for that particular thing, how they manage and what system they use. There are many instances where one part of the organization genuinely has no understanding or awareness of the activities and capabilities of another, and “we actually do that?” is a familiar refrain.

For those who are accomplished at getting things done, the tendency is to bypass process and systems, and rely on personal knowledge, relationships and workarounds. It is often far easier to send an email, make a phone call or ask a favour than it is to try to manage through official channels. Given the size of the organization, process should not only be mandatory, but it should actually be relatively efficient. The fact that process is more cumbersome than personal access says a lot about how the organization currently functions.

I know a lot about this only because I have immersed myself in exploring every part of the organization. I have interviewed extensively, taken copious notes, done a great deal of analysis and follow-up and worked to make sense of dependencies and relationships, outcomes and significance, resources and roadblocks. While I don’t pretend to have a deep understanding of any particular area as a result, what this has afforded me is a broad and comprehensive view of all areas.

The interesting thing about working in an organization like this is that you typically don’t see that breadth. Most people work within their own silo, and while they may be acquainted with people in other departments and divisions, that doesn’t result in more than a superficial understanding. Executives might have a slightly more encompassing view, but they are very often focused on their own perspectives and problems. Few have the luxury of time and or the tolerance for intense immersion that is required to build the kind of deep understanding necessary to grapple with these issues at an organizational level

This also puts me in a unique position to play the story of the organization back to its participants. It’s where my work gets exciting and challenging. What gets played back needs to be relevant. It needs to be actionable. It needs to be heard. And it needs to be accepted and taken on board. There are a lot of potential roadblocks and speed bumps getting in the way of that actually happening.

By the time I am through the process of engaging, interviewing and synthesizing perspectives from across the organization, I am in possession of a lot of information. And by that, I mean an epic and insane amount of information. Interview transcripts may run 70,000 to more than 100,000 words (so longer than an actual book). Supporting information and documentation and plans add to that. Not to mention all of the observations and insights that I gather along the way, picking up on insights, body language and culture. There are lots of dots, and I work to connect them all.

The problem is that you cannot relate them all. For all the intricate understanding I gain out of an engagement like this, there is an inherent process of filtering meaning that needs to happen. I need to identify what the story is. I need to determine a perspective and frame of reference to tell the story from. Most importantly, I need to determine the details that must be included, and those that are immediately superfluous. Creating meaning isn’t just about crafting the story you need to tell, but editing out the details that distract and don’t relate.

The balancing act here is that clarity is required for understanding, but messiness also needs to be understood. You can’t simplify the problem to a level where the solution seems easy and obvious, because that’s rarely true (although it’s possible to be excessively reductive and make it seem like its true). At the same time, you can’t make it so impenetrable that people can’t comprehend what you are saying, let alone find meaningful and actionable responses. Finding the right balance of, “this is really complicated, but I’m trying to make it easier,” is important.

There are a couple of material risks in how this is done, however. A big one is that people simply tune out, because they hear enough that is relevant and familiar that their take is, “I already know this.” They’re not wrong, in that they know some of this. They will—and need to—hear things that will speak to their world. At the same time, they need to listen beyond what they already know. They need to find and embrace and contemplate the things that don’t fit, that complexity, that make things more difficult and unpleasant and awkward.

Getting people to listen to the complex and messy is hard to do, because we don’t want to go there. Our happy place is our happy place for a reason. We like what is familiar and safe, and we’d rather not muddle around with the uncomfortable things. In fact, our brains are hardwired to do exactly this. That’s the basis of confirmation bias. We look for what we agree with, and tend to reject anything that we don’t or that doesn’t align. The consequence is that I can hold up a mirror to the organization, and what people see is exactly the image that they want to see.

The editing process that allows people to choose what they take on board functions on a number of levels. For starters, it centres on what is immediately important to them. If information doesn’t speak to their world or threatens their existence, the likelihood is that they will ignore or at the very least downplay it. At the same time, a feedback exercise depends on not only seeing the whole picture but also caring about the whole community. It needs to matter that actions taken in one part of the organization have a negative impact on experiences in another part of the organization.

The reality is that while we’d like to believe altruism exists, it does only to the extent that people are functioning in a positive space where they have the capacity and bandwidth to be considerate and helpful. As soon as things get chaotic and stressful, the idea of helping others pretty much shrinks to zero. The focus becomes on self-preservation and ensuring personal success. In our connected moments, we can help others; in our difficult times, all of our energy emphasizes protecting ourselves.

Being able to relay and explore problems of messy complexity starts with being clear about the problem that you are solving. This is its own interesting exercise. When you begin by exploring open-ended and multifaceted situations, any number of complications will present themselves. Different stakeholders will have disparate views of what is wrong, and why. They will also have diffuse and variable perspectives on what should be done about it. Keeping focus on the problem you are trying to solve—and bringing everyone else along—is absolutely fundamental.

There is another cognitive bias that you have to manage, however. It is the far more pernicious one. It draws on work that delightfully intersected the exploration of psychological biases by Kahneman and Tversky and the work on bounded rationality by James March and the Carnegie School, who are collective personal heroes of mine. Substitution bias is an important and potentially divisive influence to understand. The simple explanation of substitution bias is that when we are faced with a cognitively dense problem to solve, we substitute a much more simple and straightforward one in its place. By solving the simple problem, we allow ourselves to believe that we have also solved the complex problem.

When you describe that problem objectively and dispassionately, it seems to be wholly apparent and unsatisfying. From the inside, however, the perception is anything but. People don’t recognize the substitutions they are making in real time. In their view, they are solving the original problem. The sleight of hand that inserted a simpler challenge in its stead isn’t even obvious.

The reality is that most people believe that the simpler problem is the same as the more complex problem, and once they have figured it out then it’s solved. This is how we get incremental solutions that fix the immediate issue, but don’t do anything to appropriately address the larger complexity. The risk is that we have one more isolated solution, without in any meaningful way tackling the larger challenge .

The antidote to this is embracing the messiness knowing it is complicated and that there will be not be easy and clean answers. That’s not to say that answers don’t exist. It’s just to acknowledge that the answers that work are going to be more convoluted and are going to resist simple resolution.

Contemplating the problem means in part holding open the question for longer than you might like. You may crave an answer. You may think—in the context of your perspective—that an answer is obvious. The challenge is testing that viewpoint through the larger lens of the organization that you are a part of, and the group that you are working with. Your answer is not necessarily everyone else’s answer.

Taking the time to explore everything that is going on, from multiple perspectives, is fundamental. That may not feel natural, but it is important. It is looking at a situation from someone else’s stance, and appreciating how they may perceive the problem and the ultimate solution. More importantly, it is looking at a situation from everyone’s stance, and figuring out how best to resolve it.

Dealing with messy and complex is necessary and normal. It involves diving into a subject in detail. It requires tolerance for the learning curve, recognizing that answers will not come quickly and solutions may not be well-defined and definitively framed. This is typical, and to be expected. It requires work and effort, whether you are guiding the conversation or you are the recipient of the results.

Most importantly, it entails recognizing where shortcuts are going to be tempting, and simplistic answers are going to be appealing. These impulses, while natural, are not helpful. But they are expected. Embracing the messy and complex means first doing this for yourself, and then developing and implementing strategies for others to follow. Good answers are possible. You just need to be wiling to do the work in order to get there.