I had to give some constructive feedback recently. The work being done on a project wasn’t what was expected, there had been a number of communication challenges and prior efforts to resolve the situation hadn’t been having the desired impact. Things were getting worse, not better.

The feedback wasn’t received well. The recipient was defensive, resistant and angry. They acknowledged being frustrated by the situation, but they also felt that they were being held to an impossible standard and set up to fail. They wanted a successful project, but they didn’t like or appreciate their contribution being found wanting. They believed that they had a lot of background and experience in doing the work that they were asked to do, and they didn’t understand why this project was so different.

Feedback can be an enormous challenge, particularly to provide criticism—both as the giver and as the receiver. Truth be told, most of us don’t like being in either position. In a perfect world, we’d all do our job perfectly, everyone would love and be amazed by the contributions of everyone else, and we would be surrounded by wonder on a daily basis.

We don’t live in that world. We live in an interesting one, certainly, where many strive to make a difference and do good work. Not everyone, necessarily, but a goodly enough number do make an effort to do good work most of the time. Which might sound like it’s damning with faint praise. That actually isn’t my intention or my point, however. What I’m describing is the human condition.

Each of us, when we strive, have moments of brilliance. We produce something that is, in fact, transcendent and spectacular. Something that astound and amazes, if only because it is far better and more coherent than anything we’ve produced before, and perfectly addresses the problem that we are trying to tackle at the time.

The challenge is that each of us, by design, are cognitively lazy. We are wired to take the easy way out in most things in life. And I mean that quite literally. Our full and complete range of cognitive biases are specifically designed to make it easy to make choices. If we didn’t use them as decision making tools, we would never get out of bed in the morning, and even if we did we would quickly crumble under the weight of undifferentiated options that we were forced to wrestle with moment by moment.

The reason that we don’t face cognitive overwhelm with every decision is that we short circuit things. We go with default preferences, choose the first reasonable solution, substitute complex problems with simple ones and engage in a host of other strategies that keeps us from having to really think about things.

When we fall back on our track record of past successes, we do something very similar. That utterly spectacular and brilliant solution that we inspirationally produced last time? The next time we see a similar problem, guess what we do? Yep. We substitute in the solution that worked for us last time, and hope it works for us again this time.

What is unique about channelling brilliance in the first place is that it is creative and formative. It results from us challenging a problem, dissecting it in new ways and formulating new insights into solutions. We develop new possibilities, we try new approaches, we experiment and play with options and we finally something that works in a profound and meaningful way.

Every other instance of a similar problem, we skip pretty quickly over the wrestling and experimenting stage. To the greatest degree possible, we go from the problem identification to the solution selection stage. In doing so, we hope our past brilliance will shine with the same luminosity in dealing with the current circumstances. The sad reality is that what we are proposing has probably lost a lot (or at least a substantial amount) of its lustre.

That’s a frustrating reality for many of us. Mostly because it means the only way to be successful in any given circumstances is to do the work necessary to address what is specific and unique about that particular problem.

That is also, I think, when most of us find criticism and feedback to be so difficult to receive. It means that we are not done. It means we need to do more work. It means that we didn’t produce a brilliant masterpiece the first time. Not that this should ever really be a surprise. But it’s an astonishingly lingering sentiment, nonetheless.

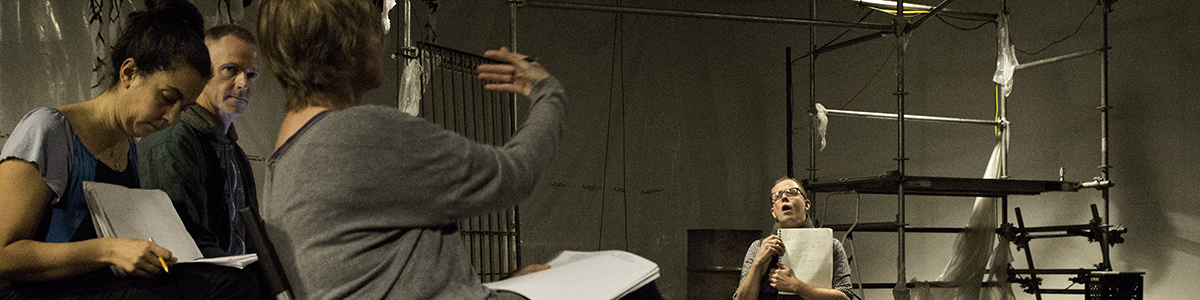

I was reminded of this last night, watching a very different form of providing constructive feedback take place. By way of context, I’m on the board of directors of a theatre company in Toronto. Last night was their dress rehearsal. They had spent the day working through a number of scenes, still exploring, still shaping and still preparing. Just before the dinner break, the director provided “notes.”

Giving notes is the process of providing feedback, suggestions, recommendations and insights in rehearsing a play. It happens with the entire cast. The director moves through the notes that they have made, in the sequence they have made them, to the person they are intended for, point by point. Observations are offered, instructions are provided, suggestions are made.

An example might be something along the lines of, “Sarah, when you moved while you were saying this line, I found it distracting. Move, stop, say the line. Keep your hands still. And give your attention to the audience stage right.” It might also be something along the lines of, “Daniel, for this line, make it sound like you aren’t really sure what you’re talking about.” Notes can be very specific and precise, and they can be maddeningly vague. They are trying to get at the essence of an idea, and at the time, neither the director or the actor might have a fully formed picture of what that idea actually is.

But this is the point of the rehearsal process, discovering the play and trying to produce the very best outcome possible. Sometimes notes contradict each other. There are times when an actor responds, “But you told me to stop doing that two days ago, and now you want me to do it again.” And the director will often look up, nod, and reply, “Yup. I was wrong then. Of course, I might still be wrong. But let’s try it this way again.”

What struck me about the process was the earnestness and intensity of the conversation. The company in question is composed of incredibly talented actors. They routinely work on other projects, for other companies. They are well known and respected, most particularly amongst their peers in the theatre industry. They appear not just on stage, but in movies and television. These are people that know what they are doing, and have incredible talent, passion and range.

Despite their talents, they listen, they accept feedback and the know they can improve. In fact, I would argue they do that because of their talents. They know and trust the process. They come to the process with the willingness to discuss, explore and work—over and over again—one interaction that is perhaps sixty seconds long, in order to get it right. To make it as meaningful and relevant as possible. They don’t just talk about what and how, but why they are doing what they are doing. They seek meaning and value. They question whether what they are doing makes sense. And they try it again.

What is most remarkable is the manner in which the actors approach the process of doing notes. Their attitude of receiving feedback isn’t defensive or negative. It’s open, considering and receptive. There is no anger or resentment. There is a willingness to consider, and a mindset of, “This will make it better.” It is a process of building up, not one of tearing down.

The act of building up, of course, might genuinely be destructive in its own right. Days and weeks of work might be changed, based on a new insight. An entire scene might be reinterpreted, reworked or excised in its entirety in order to make the play as a whole better. That is a mindset that is not simply accepted, but actually embraced. It’s a common mindset in the arts, but its one that I often see resisted elsewhere.

Watching a company of talented actors at the end of a twelve hour day dive into a process of creative interpretation is watching people that genuinely care about making their work the best that they possibly can. They are—for the most part—not just doing what worked for them the last time. They are willing to challenge the core assumptions of what they are doing and why, and to tear down and rebuild their roles, their approach and their interpretation where it makes sense to do so.

That’s a very different approach to receiving and processing constructive feedback. It also brings to mind several suggestions of how to rethink how the rest of us provide, receive and process feedback in dealing with our own roles, projects and jobs.

A big part of the problem that we need to tackle is about getting ego out of the way. In fact, this is probably the single biggest challenge we face in making constructive feedback actually successful. We need to be able to accept that the feedback, critical though it may be, is about the work. It’s not a judgement of ourselves, or our skills and experience or our worth.

Our skill, experience and track record are what got us to the table. What keeps us at the table is what we do once we are there. That has a couple of key implications. For starters, being in the room is not an entitlement; it’s earned. Our past record may have determined whether we got the invitation to cross the threshold, but it’s not what keeps us there. Our on-going status is shaped by what we actually do while we’re there, by the quality of the work and the manner in which we collaborate and contribute. In this, the bromide is true: we are truly only as good as our last project.

As well, regardless of our talent, each of us has room and opportunity to improve. And each of us can benefit from receiving objective insight. The best in any given field know this to be a fundamental truth, and embrace it willingly. The attainment of mastery as much as anything involves an appreciation of how much more there still is to learn. But that can be a relatively intimidating realization to make as well. It means that moving forward requires continued learning and growth.

To do this, we need to know where and how we can improve. That requires not just embracing but actually seeking out constructive feedback. We need to appreciate that criticism and critique aren’t negative and to be avoided, but are the very insights we need to grow and improve. This is a big shift for a lot of people. But it’s a powerful one when we can make it.

The actors I witnessed yesterday illustrated very clearly a path to accepting criticism gracefully. To a person, they approach it from a perspective of gratitude and thanks. In fact, “OK, thanks! I’ll try that!” was the most common response after a note was given. The mindset that makes this possible fundamentally recognize that the input received is focussed on, “How can this be better?” And that getting better involves continual work, and a willingness to shape and re-shape, until you arrive at the right answer for that particular problem.

Hi Mark – I think it is worth noting the form of the feedback given in your example. In each case, the director was very clear about what the desired behavior was. Sometimes he identified the undesirable behavior, but even then went on to identify what to replace it with (eg. “you moved”… next time “stop and deliver your line”).

It’s often easy to identify what we don’t like, but more difficult to identify the desired behavior.

Good article!

Hi, Mark,

Theatre has the expectation of feedback on a daily basis. Most of us experience it only annually or when something has gone south. Why? My knee jerk reaction says it is an issue of not enough time, but it is really a question more of priorities. As a manager, is my first priority to develop my staff, and, if so, is it a daily, quarterly or annual priority.

Worth thinking about. Thanks for the post.

Roger